I've been profoundly affected by loss from suicide, as so many have been. I'm in this particular memory as I sit here to share during Suicide Prevention Awareness Month—21 years into my own recovery, but not so distant from the experiences I've lived through to make it here.

He had just turned 27 two months before his death. I was turning 27 the month he died. We had been friends for five years but it felt like we had known each other forever. He had a wife and a young daughter.

He was the type of friend that was always supportive, loving, generous and encouraging. He loved animals and children and art. He was funny, kind, and sensitive.

We had been through a lot together in our early 20’s. Break-ups, weddings, births, deaths. But this event was one we would both go through alone. I was so angry, then I was disappointed in myself for being angry. How could someone so young with so much to live for and so much to look forward to just give up? How did he not have hope? How could he leave his daughter?

Then the waves of I should’ve, could’ve done something—but what? I still don’t know the answer. That question plagued me for years. I just didn’t know at the time that he was in so much pain, suffering from depression, addiction, and the pressures and responsibilities of so much fame so young. I had just gotten into recovery myself and was on shaky ground. I knew I couldn’t be around him and not use drugs with him, so I stayed away that last year of his life.

During that year we both became parents. My life had gotten much better, his had gotten worse.

The world had expectations of him that he didn’t think he could live up to. There was an intervention convened for him that he thought was full of hypocrites—friends and family that were on his payroll, some just as dependent on drugs as he was. At the intervention they told him he was a bad father and he was a danger to his daughter. They told him his band would leave him, that his wife would leave him, and that all his friends would wash their hands of him unless he went to rehab. This was the typical protocol of a standard intervention (one particular model of intervention, anyway).

There was a trip to rehab in California, and for a moment we all breathed a sigh of relief. He’s safe now, he’ll get well there. He will get the help he needs. Then he went out for a smoke and jumped the wall and flew home to Seattle. Very few people saw him after he returned, and those that did were not the types to give up information easily. I got the call that he was missing and there were people searching for him. They asked if I had any idea where he might be. If there were any friends I was in contact with that might have seen him recently. I called his house multiple times and left messages. All the while he was in the room above the garage, getting high and planning his final moments on this earth.

The whole world loved him, called him the voice of a generation. He had love and adoration from strangers and family and friends. He had fame and money, lots of it. He had a career. He had talent. He had a wife and a daughter that he loved. None of it mattered in his final assessment of himself.

The darkness and despair wouldn’t allow him to find a reason to live, a reason to believe things might get better, that he could get help and relief from the depression and addiction that had plagued him his whole adult life. It robbed him of the hope that he could change, that things could change.

I truly believe everyone had the best intentions, but just didn’t know what to do. For so many families and loved ones the only available options seem futile, but it’s something. The way he heard their threats and ultimatums made him believe everyone was better off without him. He thought the world didn’t need him. After his suicide, his wife said she wished they had not given him “tough love”—she said she wished they would have just given him love.

Our kids are now 27, the same age we were when he died. They seem so young, so full of life. They are both healthy and happy. I often think of him, especially on the birthdays of our children and how my son got to grow up with his mom, but his daughter missed out on a life with her beautiful, generous, talented, and amazingly loving father.

Our children have only met once, as babies, on the day of his funeral. But I know he is watching over both of them, sending them love and protection from his perfect, loving, beautiful soul.

I am eternally grateful to be writing this with the perspective granted from 21 years of recovery from substance use disorder. The stigmas attached to suicide, mental health challenges, and substance use disorders still exist—but as we are more transparent about our own experiences and healing, there is hope that those suffering will feel more empowered to seek help and support.

If you are experiencing a mental health crisis or domestic violence, but aren’t sure where to turn, you can text “HOME” to: 741741 in the US, 686868 in Canada, or 85258 in the UK to get connected to someone right now. https://www.crisistextline.org/texting-in

Emphasize your product's unique features or benefits to differentiate it from competitors

In nec dictum adipiscing pharetra enim etiam scelerisque dolor purus ipsum egestas cursus vulputate arcu egestas ut eu sed mollis consectetur mattis pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus mauris aliquam ornare nisl purus at ipsum nulla accumsan consectetur vestibulum suspendisse aliquam condimentum scelerisque lacinia pellentesque vestibulum condimentum turpis ligula pharetra dictum sapien facilisis sapien at sagittis et cursus congue.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

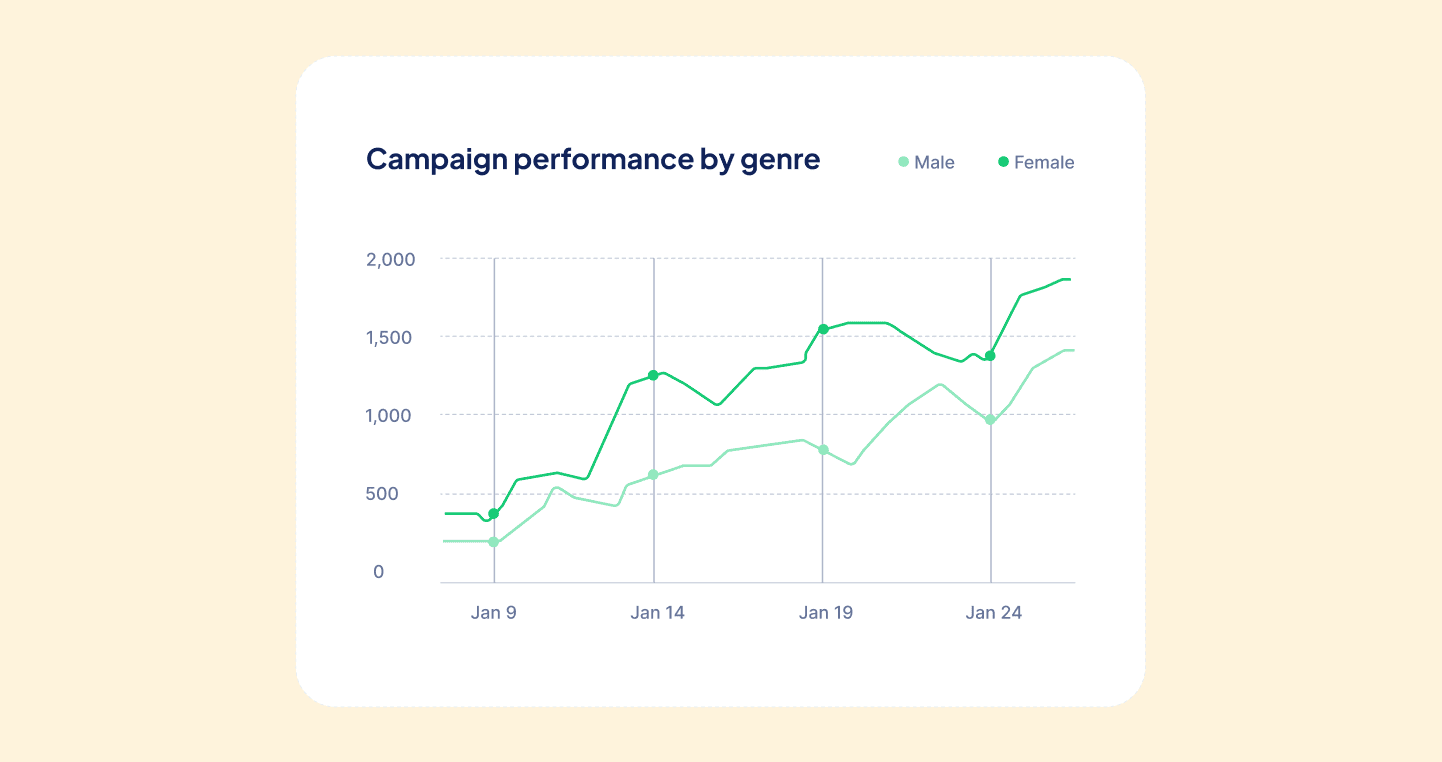

Incorporate statistics or specific numbers to highlight the effectiveness or popularity of your offering

Convallis pellentesque ullamcorper sapien sed tristique fermentum proin amet quam tincidunt feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Use time-sensitive language to encourage immediate action, such as "Limited Time Offer

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Address customer pain points directly by showing how your product solves their problems

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Vel etiam vel amet aenean eget in habitasse nunc duis tellus sem turpis risus aliquam ac volutpat tellus eu faucibus ullamcorper.

Tailor titles to your ideal customer segment using phrases like "Designed for Busy Professionals

Sed pretium id nibh id sit felis vitae volutpat volutpat adipiscing at sodales neque lectus mi phasellus commodo at elit suspendisse ornare faucibus lectus purus viverra in nec aliquet commodo et sed sed nisi tempor mi pellentesque arcu viverra pretium duis enim vulputate dignissim etiam ultrices vitae neque urna proin nibh diam turpis augue lacus.

%202.svg)