When I first found recovery, I was taught to refer to myself as an addict. This is common practice among those in the pathway of recovery that I used to begin my journey. After a few years in recovery, I began to learn about recovery advocacy and the importance of referring to myself as a “person in recovery” rather than an “addict.” Each time I said that I felt a little uncomfortable, because the natural follow-up to that phrase would be to then say what exactly I was in recovery from; this was a complex concept for me. Substance use disorder was one thing I was recovering from, yes—but I also experienced depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Along with a difficult childhood, these disorders all caused harm in my life and prevented me from reaching my potential (or even thinking that I had potential).

Then one day, I was in an all-recovery meeting and heard someone say they were in recovery from self-destruction. The moment I heard that, I immediately identified with it.

I grew up in a family that was not healthy; our substance use disorder runs generations deep. For me, the unfortunate result of that was that I was not given access to the tools needed to be happy and healthy. My achievements were never recognized; I vividly remember my mom always throwing away any trophies I earned through winning competitions. The only feedback I received was negative and hurtful, so it was natural that I didn’t have a positive view of myself. Accepting compliments was uncomfortable and difficult for me—sometimes, I still have difficulty accepting compliments. Seeing potential in myself was completely out of the question. I lived the first 40 years of my life without being able to accept success. I was constantly self-sabotaging out of fear of success. I also spent those years “playing the victim” and blaming my family for everything that went wrong.

And then I found recovery. I realized that those tools for achieving my personal potential for health and happiness hadn’t been given to me because my mother, too, was denied them throughout her own childhood. I found people who understood me instead of dismissing me. I found people who supported me, women who came to court with me to help me find the courage to tell the judge that my husband was physically harming me. I found an environment that allowed me to grow: people that supported me when I wanted to self-sabotage, people who showed me how to embrace success. Through my recovery process, I learned that yes, I do have potential. I met people who encouraged me to reach ever higher in pursuit of my goals.

It was only through this process and the growth I experienced that I was able to learn to be a parent to my own children. Through recovery and this supportive community, I learned what unconditional love meant: how to give it as well as how to accept it. Once there, I learned how to chase my dreams without guilt. I began to understand that it was OK to have dreams and that I could realize them. I stopped playing the victim, took control, and held myself accountable for my life. I gained freedom from the pain and damage that once ruled my life.

Today, I am no longer living in self-destruction. I have a purpose and am filled with gratitude for what my recovery journey has given me. Today, I live in hope.

Emphasize your product's unique features or benefits to differentiate it from competitors

In nec dictum adipiscing pharetra enim etiam scelerisque dolor purus ipsum egestas cursus vulputate arcu egestas ut eu sed mollis consectetur mattis pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus mauris aliquam ornare nisl purus at ipsum nulla accumsan consectetur vestibulum suspendisse aliquam condimentum scelerisque lacinia pellentesque vestibulum condimentum turpis ligula pharetra dictum sapien facilisis sapien at sagittis et cursus congue.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

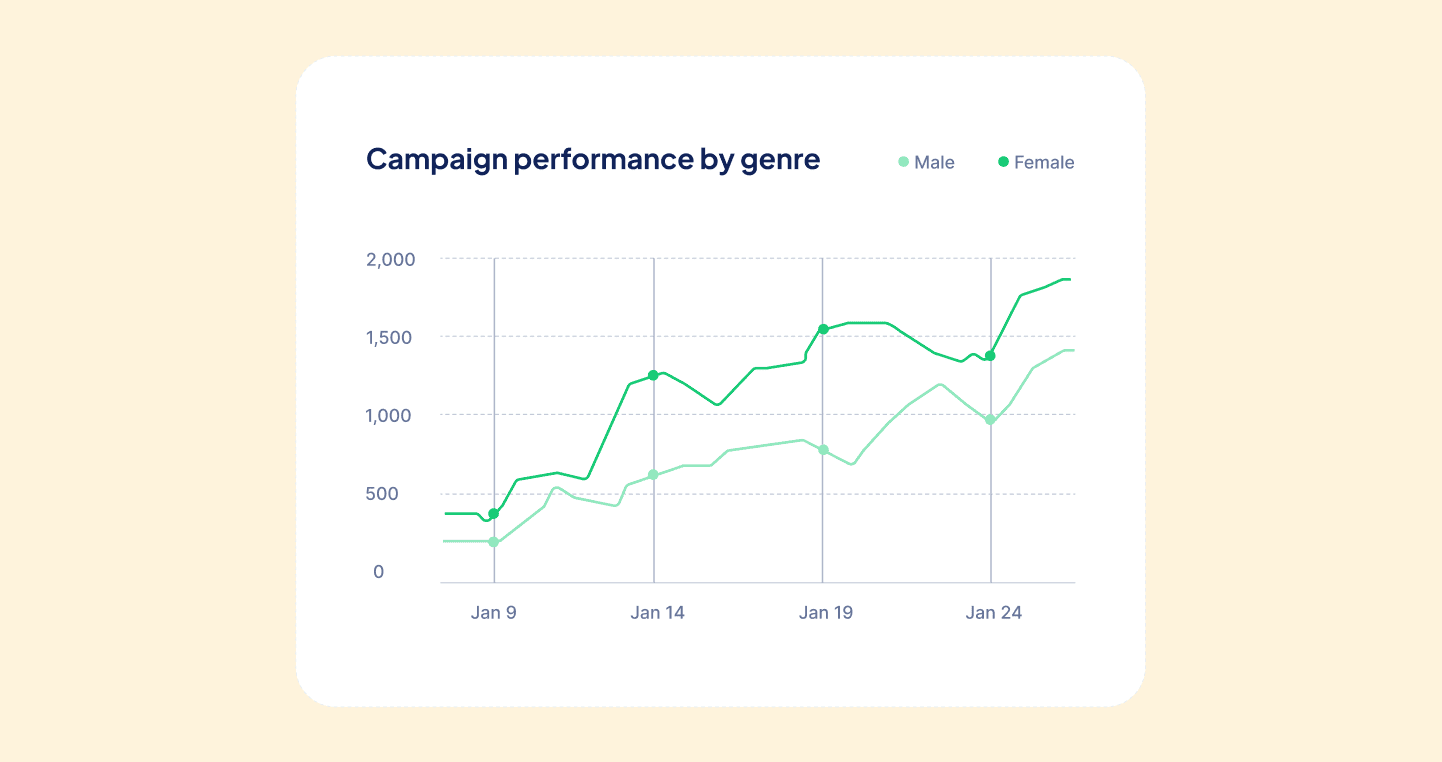

Incorporate statistics or specific numbers to highlight the effectiveness or popularity of your offering

Convallis pellentesque ullamcorper sapien sed tristique fermentum proin amet quam tincidunt feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Use time-sensitive language to encourage immediate action, such as "Limited Time Offer

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

- Pharetra curabitur et maecenas in mattis fames consectetur ipsum quis risus.

- Justo urna nisi auctor consequat consectetur dolor lectus blandit.

- Eget egestas volutpat lacinia vestibulum vitae mattis hendrerit.

- Ornare elit odio tellus orci bibendum dictum id sem congue enim amet diam.

Address customer pain points directly by showing how your product solves their problems

Feugiat vitae neque quisque odio ut pellentesque ac mauris eget lectus. Pretium arcu turpis lacus sapien sit at eu sapien duis magna nunc nibh nam non ut nibh ultrices ultrices elementum egestas enim nisl sed cursus pellentesque sit dignissim enim euismod sit et convallis sed pelis viverra quam at nisl sit pharetra enim nisl nec vestibulum posuere in volutpat sed blandit neque risus.

Vel etiam vel amet aenean eget in habitasse nunc duis tellus sem turpis risus aliquam ac volutpat tellus eu faucibus ullamcorper.

Tailor titles to your ideal customer segment using phrases like "Designed for Busy Professionals

Sed pretium id nibh id sit felis vitae volutpat volutpat adipiscing at sodales neque lectus mi phasellus commodo at elit suspendisse ornare faucibus lectus purus viverra in nec aliquet commodo et sed sed nisi tempor mi pellentesque arcu viverra pretium duis enim vulputate dignissim etiam ultrices vitae neque urna proin nibh diam turpis augue lacus.

%202.svg)